Apprenticeships could be the ideal employment route for homegrown talent for whom traditional schooling has failed, as well as to attract young talent that prefer a more practical path to employment; however, the Government’s policy approach is actively freezing these people out of these routes to the labour market at a time when they are most needed.

Introduction

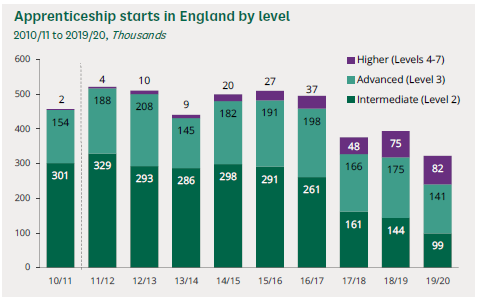

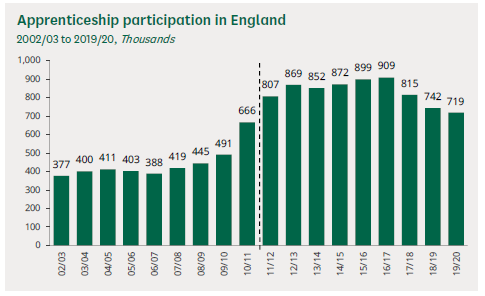

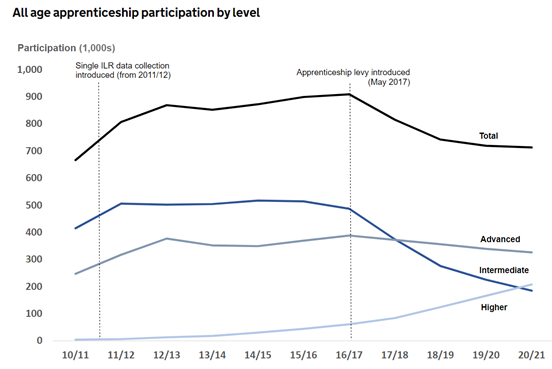

Apprenticeships are the longest standing and most well-known vocational courses for the business community [1]. Nevertheless, starts in apprenticeships have been in decline since 2015/16 – when there were 509,360 starts [2]. In comparison, there were 321,400 starts this year (2020/21) down 0.3% from last year (322,530) – even considering that 2019/20 numbers were particularly bleak due to the pandemic. Learner participation has also been in decline over recent years, 713,000 learners were participating in an apprenticeship this year, 0.8% less than in 2019/20, and down from the 908,700 peak in 2016/17.

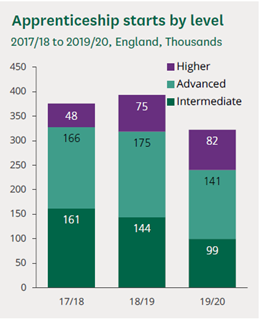

The decline in apprenticeships starts and participation is worrying for economic and social reasons, as they have the potential to act as vehicles of social mobility [3]. The decrease is driven by the cut in the availability of courses and starts in intermediate apprenticeships (Level 2, equivalent to GCSEs) and young people participation (under 19 and 19 to 24 years old).

Entry level apprenticeships are the most used by the youngest, especially school leavers and those from disadvantaged areas, acting as their first step into the post-16 education and employment ladder [4]. However, the pattern of apprenticeship participation has seen a marked shift and they are now being increasingly used by older, employed, and higher skilled workers – at the expense of younger, less skilled workers.

In a time when the country’s economy is in dire need of vocationally trained individuals with industry skills, the structural lack of provision and capacity to attract young people to entry level vocational routes is a likely drag on the UK’s current and future productivity and economic competitiveness.

Latest numbers

In contrast to the Government’s rhetoric on levelling up, only 26% of apprenticeship starts were at Level 2 (intermediate) in 2020/21, down from 31% last year, and a sharp decline from 60% in 2014/15. Conversely, the number of higher apprenticeships (Level 4 and above) has increased substantially since the introduction of the apprenticeship levy [5] in May 2017, jumping from 13% in 2017/2018 to 31% of all starts this year, and more than doubling in absolute numbers from 48,000 (2017/18) to 98,810 (2020/21).

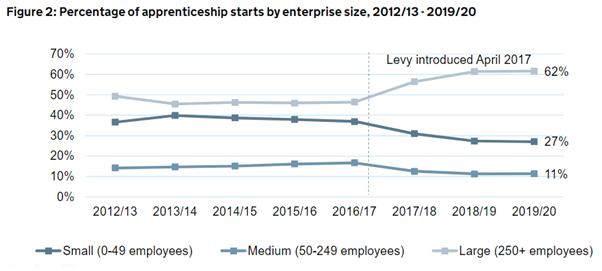

Higher apprenticeships were the only level that increased in absolute numbers during 2019/20, the toughest year of the pandemic, whilst intermediate and advanced apprenticeships lost 45,000 and 34,000 starts respectively. This is likely to be driven by larger employers using the levy funds to train their existing staff at higher level apprenticeships.

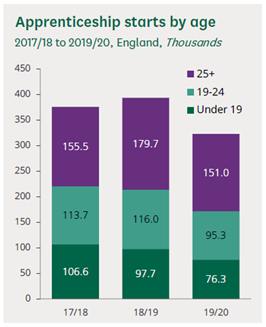

In 2020/21, 50% of the apprenticeships started were by people aged 25 and over, versus 20% started by those under 19, accelerating the age polarisation trend. Starts among those under 19 dropped the most in the last two years, with 33% fewer starts in 2020/21 than in 2018/19. In comparison, starts for the 19 to 24 cohort fell 18% and for those aged 25 and over only 10%.

Policy changes

Over the last 5 years, apprenticeships have undergone significant reforms, such as the introduction of the apprenticeship levy in May 2017; the requirement for apprenticeships to have a duration of at least 12 months with 20% off-the-job training [6]; the requirement for all apprentices to achieve a Level 2 Maths and English qualification by the end of their apprenticeship; and the gradual replacement [7] of previous “frameworks” model with new apprenticeship “standards”, linked to an end-point-assessment.

These changes fell short by almost a million [8] to meet the “3 million apprenticeships by 2020” target pledged by the Government in 2015, and failed to make apprenticeships work for young people and SMEs.

For example, the introduction of the end-point-assessment has increased the quality evaluation of apprenticeships, helping with raising their perceived value with employers. However, this push towards a more rigorous “standards” model without enough entry level opportunities to support those less academically driven, is leaving behind many who via accessing the programme could have played an important role in their local labour market.

Policy implications

Not only have the overall numbers in apprenticeship starts and participation fallen in the last 5 years, these reforms, particularly the levy, have had an unintended consequence of “middle class capture”. It is pushing large firms to use their levy funds to train existing employees in higher level apprenticeships – shifting apprenticeships in England towards a retraining/upskilling tool for the employed and away from school leavers, the unemployed and those who lack the skills to access the labour market.

Apprenticeships, previously widely used by young people and SMEs, are becoming increasingly dominated by older employees and larger companies; which are the area of the economy that needs the least support. The Government changes to the programme, together with the introduction of the Digital Apprenticeship System, have made the apprenticeship landscape too complex for smaller firms to navigate without assistance, which they often cannot afford.

Furthermore, the performance of apprenticeships is now also failing to meet the largest post-Brexit need of addressing shortages in lower level skills provision in critical areas of the economy. Colleges and Independent Training Providers have been dropping Level 2 apprenticeships courses due to the Department for Education’s insistence that all apprenticeships meet Level 3 standards, on the basis of Level 2 courses being poor quality, as well as due to cuts in entry level courses funding bands – deepening the labour market mismatch between the workforce skills set and employment demand.

For instance, we have heard from colleges having to drop Level 2 Plumbing courses in favour of the Level 3 alternative; however, Level 3 Plumbing courses focus on high technical outcomes, such as fitting complex boiler systems, which do not adjust to the labour demand from developers struggling to recruit entry level plumbers to complete housebuilding projects. Another college admitted having to discontinue their social care apprenticeship courses because they could not cover the costs and the delivery method did not adjust to the industry needs, leaving inconsistent provision and poor quality to those that remain.

Source: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/apprenticeships-in-england-by-industry-characteristics/2019-20

Source: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/apprenticeships-and-traineeships/2020-21

Conclusion

Given the long term structural failure of the UK to provide good quality vocational routes to skills and employment in comparison to other OECD countries, such as Germany, this is a perverse outcome for a large cohort of young people that are not able or do not want to access higher education. It also makes it harder to encourage those who might be considering higher education to pursue a vocational training alternative.

Short term incentives can be useful as a temporary solution, but the current post-16 education needs sustainable and long-term funding and policies that encourage SMEs to take and retain apprenticeships, as well as high-quality entry level courses with solid prospects, to convince school leavers and those under 24 to follow a vocational path.

At a time when the country is setting the foundations for the post-Brexit and post-pandemic economy, if the Government is serious about “levelling up”, it is imperative to refocus the programme towards SMEs and post-16 education to ensure a productive, skilled, and more equal society and economy for the years to come.

Footnotes:

[1] Business West QES Q3 results

[2] All numbers refer to England only

[3] National Foundation for Education Research (NFER), Putting Apprenticeships to Work for Young People (2021)

[4] Social Mobility Commission, Apprenticeships and social mobility (2020)

[5] Apprenticeship Levy: Employers who spend more than £3m annually on wages must pay 0.5% of their payroll above the £3m threshold. This money is topped up with an extra 10% from government funds and kept in a digital account for each employer to deploy on its own apprentices. Funds that are not used by the employer within 24 months are given to HMRC.

[6] Equivalent to approx. 1 day per week (subject to each apprenticeship agreement details)

[7] Starting from 2015 to 2020

[8] There were just over 2 million starts from May 2015 to January 2020 (Department for Education, January 2020 Apprenticeships and Traineeships statistics in England)

- Log in to post comments