At a recent Brexit-themed event organised by Business West, a member of the audience working in the agricultural sector posed an interesting question to the panel of experts. If the UK and the EU successfully manage to negotiate a Free Trade Agreement following their divorce, and the UK subsequently strikes a trade deal with another country, say New Zealand, then what’s to stop a crafty Kiwi farmer from exporting his goods to the UK and then re-exporting them on to Europe – piggybacking on Britain’s preferential trading terms with the EU and bypassing the bloc’s notoriously hefty tariffs on agricultural products? Put another way, in a post-Brexit world, how could the EU trust that goods coming from the UK are actually UK goods, legitimately laying claim to the low rates of duty that the government hopes to secure?

Unfortunately for our hypothetical farmer, the brains behind the rules of international trade have an answer to this. Rules of origin, or ‘ROOs’, require exporters to prove where their goods originate, and they’re something which all EU-exporting businesses in the UK will need to get up to speed with as part of their preparations for Brexit. This is especially true since identifying ‘origin’ for some goods can be more complicated than you might think.

Why does this matter now?

At the moment, as a member of the EU’s customs union, any goods entering the UK from outside Europe (from countries with which the EU does not have a Free Trade Agreement) have a fixed tax slapped on them which is common to all member states. Once this Common External Tariff (CET) has been paid, the goods are free to move across the single market without further duties or customs checks.

Now that we’re leaving the EU and its customs union, the UK will no longer need to apply the CET, allowing it to strike up trade agreements with other countries around the world. This means, though, that if as is hoped a UK-EU FTA is negotiated which allows for tariff-free trade between the two parties, the EU will want to ensure that other countries (with which the UK might have more favourable trading terms than the EU) are unable to use the UK as a back door for accessing the single market and avoiding the CET. To do this, EU customs authorities will require proof of where UK exports actually come from. So when we leave the EU, UK products will only be able to enjoy tariff-free access to the single market if it can be proved they originate in the UK.

Many UK exporters will have already come across certificates of origin, of which there are two kinds. Non-preferential certificates are required for exporting to certain non-EU states, stamped by chambers of commerce to confirm where the last major manufacturing stage took place in a product’s production. While these certificates are unlikely to be affected by Brexit, what will be significant if and when a UK-EU trade deal is signed is preferential origin – the rules for which will be new to the majority of British exporters.

So what’s meant by ‘origin’?

Waiting to be dispatched at Dover, a consignment of Granny Smith’s grown halfway around the world clearly isn’t going to qualify as UK produce in the eyes of EU customs officials. But if a bakery in Gloucester were to use New Zealand fruit to make apple pies for export, no one’s going to claim that the finished pastries aren’t British. Generally speaking, preferential rules of origin require that non-originating materials are sufficiently worked or processed in order for the exported product to be deemed originating in the country where that processing took place. Put simply, you need to show that you’ve done something significant with any materials you’ve imported if your goods are to be eligible for reduced tariff rates upon export.

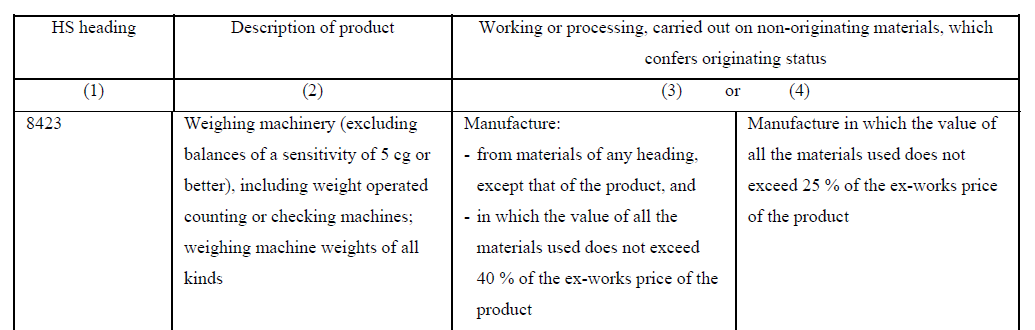

As to what constitutes ‘sufficient processing’, the rules can be quite complex. Every category of product, as classified by its unique tariff or ‘HS’ code, has a specific rule for conferring origin attached to it. Often this will say that a certain proportion of the product’s final value must come from the work done in the country in question – 60% local value added is a typical requirement. Another common signifier is a change to the tariff code at heading level brought about by the processing of the non-originating materials. If I wanted to export weighing scales, for instance, the relevant ROO shows me that both these criteria need to be met if the goods are to gain originating status, or alternatively if the value of the imported materials (including parts falling under the same HS heading) doesn’t exceed 25% of the final price:

Source: The European Free Trade Association

What does this mean for me now?

This might all sound like a bit of a headache, but it’s worth remembering that these rules will only come into force once a UK-EU trade agreement is struck, which won’t be until 2019 at the earliest. If you currently export to countries with which the EU has FTAs, like Mexico or South Africa, then you’ll already be familiar with preferential ROOs and their accompanying documentation (normally EUR.1 certificates) – giving you a big head start in adjusting to the new arrangements post-Brexit. It’s also important to note that most agreements of this kind include so-called cumulation rules, which allow exporters to add within-FTA content to local content in order to meet the ROO requirements. This would mean that for UK companies, materials imported from within the EU would effectively count as UK materials when exported back into the bloc – hopefully making it less challenging to satisfy origin criteria for firms embedded within European supply chains. Finally, it’s often the case that low value exports are exempt from proving origin, or the procedures for gaining preference are at least a little easier.

These details will all be subject to negotiation, but it’s clear that exporters who source materials or components from around the world would be wise to start giving these rules some consideration sooner rather than later. Without contributing sufficient value added, your goods won’t be eligible for any tariff preference negotiated in a future UK-EU trade agreement.

Beyond the question of tariffs, unfortunately there’s no escaping the fact that ROOs will bring some additional paperwork for UK exporters selling to the EU market. While it’s not clear exactly what form this will take – whether each of your shipments will need certification or your company will have to apply for special ‘approved exporter’ status – you’ll need to be prepared to prove the origin of your products to HMRC. This will mean supplying details of your raw materials, where they’ve come from, the processes you’ve carried out on them and the value you’ve added.

At this stage, since a deal with the EU on ROOs is yet to be inked, making detailed preparations in this area won’t be easy. But it would be prudent to start thinking about these issues at a strategic level and taking proactive steps to ensure that your business is in a strong position to adapt to the new requirements when the detail emerges. Ensuring you have a sound understanding of your supply chain would be a useful first step, perhaps getting declarations of origin from your suppliers to help establish where all your content has come from. Looking at the EU’s standard ROO requirements for your products and thinking about the value you’re adding should give an indication as to whether you’ll be eligible for the tariff preference, and if necessary, it may be worth considering if it’s possible to source some of your imported materials more locally. This way you can get ahead of the game and make sure that when the changes come, you’ll be well placed to deal with them.

- Log in to post comments